The Pacific Paradox: When Warm Water Feeds the Ocean

Source PublicationNature Communications

Primary AuthorsAn, Laws, Liu et al.

You likely view El Niño as a suffocating blanket for the ocean. The standard logic is simple: warm water creates a cap on the surface, preventing cold, nutrient-rich water from rising up. Without those nutrients, phytoplankton die, and the entire food web crashes. This has been the accepted story for years.

But nature rarely follows a single script. A new analysis of two decades of data reveals that in the Western Tropical Pacific, the exact opposite occurs.

The Unexpected Feast

Researchers looked at field observations, satellite data, and Earth system models. They found that during El Niño events, the Western Pacific does not starve. It feasts. Chlorophyll concentrations rise, and populations of diatoms—a crucial type of phytoplankton—surge.

When the climate cycle flips to La Niña, which usually brings cooler, productive waters elsewhere, this specific region sees a decline in life. It is a complete reversal of the pattern seen in the Eastern Pacific. The question is: how does life bloom when the water is warm?

The Eddy Effect

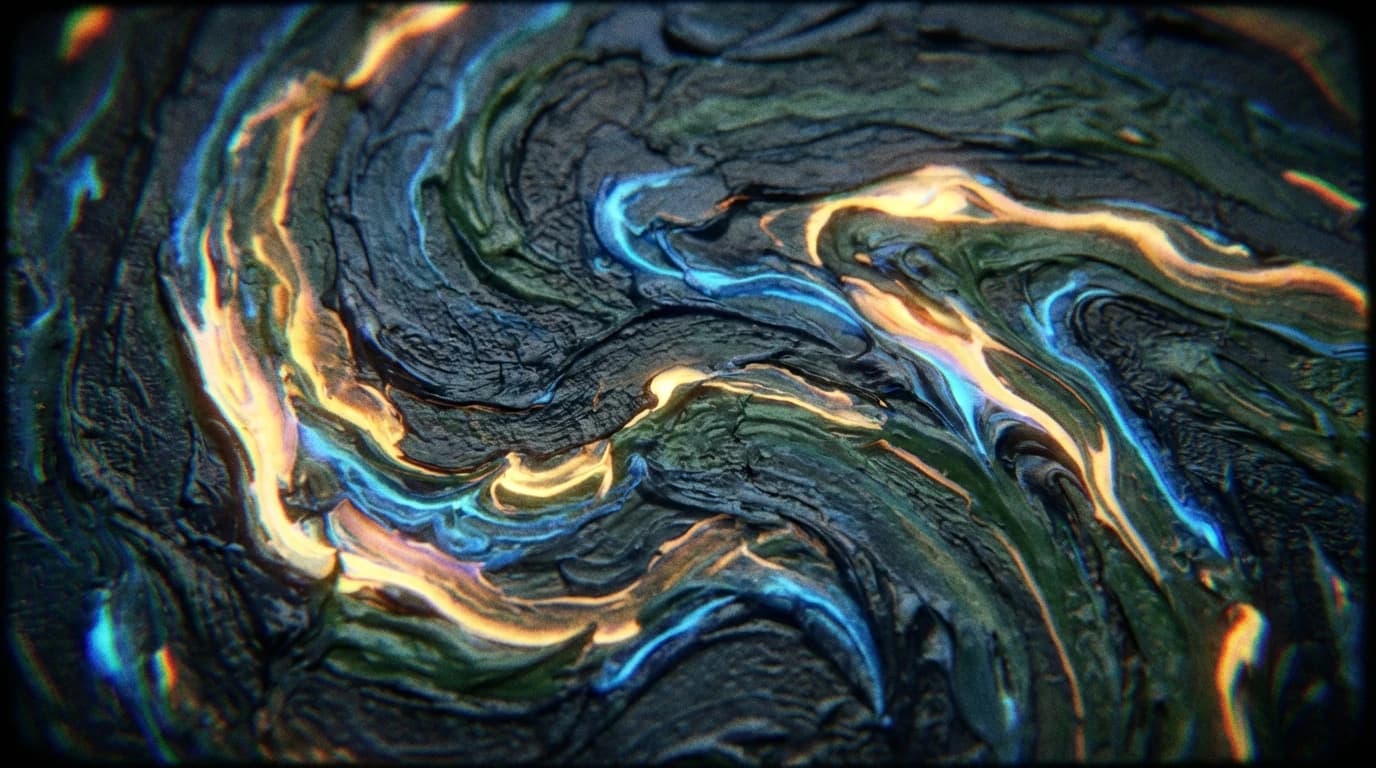

The answer lies in the physics of the water itself. The study identifies a mechanism involving 'eddy activity'. Think of these as massive, swirling whirlpools in the ocean. During El Niño, and amplified by the longer-term Pacific Decadal Oscillation, regional circulation changes.

These shifts kickstart the eddies. Instead of the water sitting stagnant under a warm layer, these swirling currents act like pumps. They facilitate upwelling, physically dragging nutrients up from the deep despite the surface warmth. This injection of fertiliser stimulates production, allowing diatoms to thrive where we once expected a desert.

Correcting the Forecast

This matters because our current climate models are often too simplistic. If we assume warm events always reduce biomass, our predictions for fisheries and carbon absorption in the Pacific will be wrong. The Western Tropical Pacific is a massive engine for marine life.

To manage these ecosystems sustainably, we must recognise that physical forces like eddies can override temperature constraints. Climate change predictions need to account for these complex, regional gymnastics, rather than applying a blanket rule to the entire ocean.