The Chameleon Chip: Rewriting the **Electronic Properties of 2D Materials**

Source PublicationPhysical Chemistry Chemical Physics

Primary AuthorsLai, Wang, Niu

The Silent Tyrant of Silicon

Consider the rigidity of a stone. Once carved, it remains fixed. For seventy years, the foundation of our digital age has mimicked this stubborn permanence. A semiconductor is born with a specific destiny, dictated by its atomic lattice. It is either a conductor or an insulator, defined by a fixed energy gap that refuses to budge. Engineers fight this static nature daily. They etch, they dope, they heat. Yet, the material resists. It generates waste heat—the scream of electrons forcing their way through a lattice that does not want them. This is the silent adversary of modern computing: the immutable bandgap. It limits how small we can build and how cool our devices run. We are trapped in a marriage with materials that cannot change their minds. They are stiff, brittle, and uncompromising. To build the future, we need something that breathes.

Controlling the **Electronic Properties of 2D Materials**

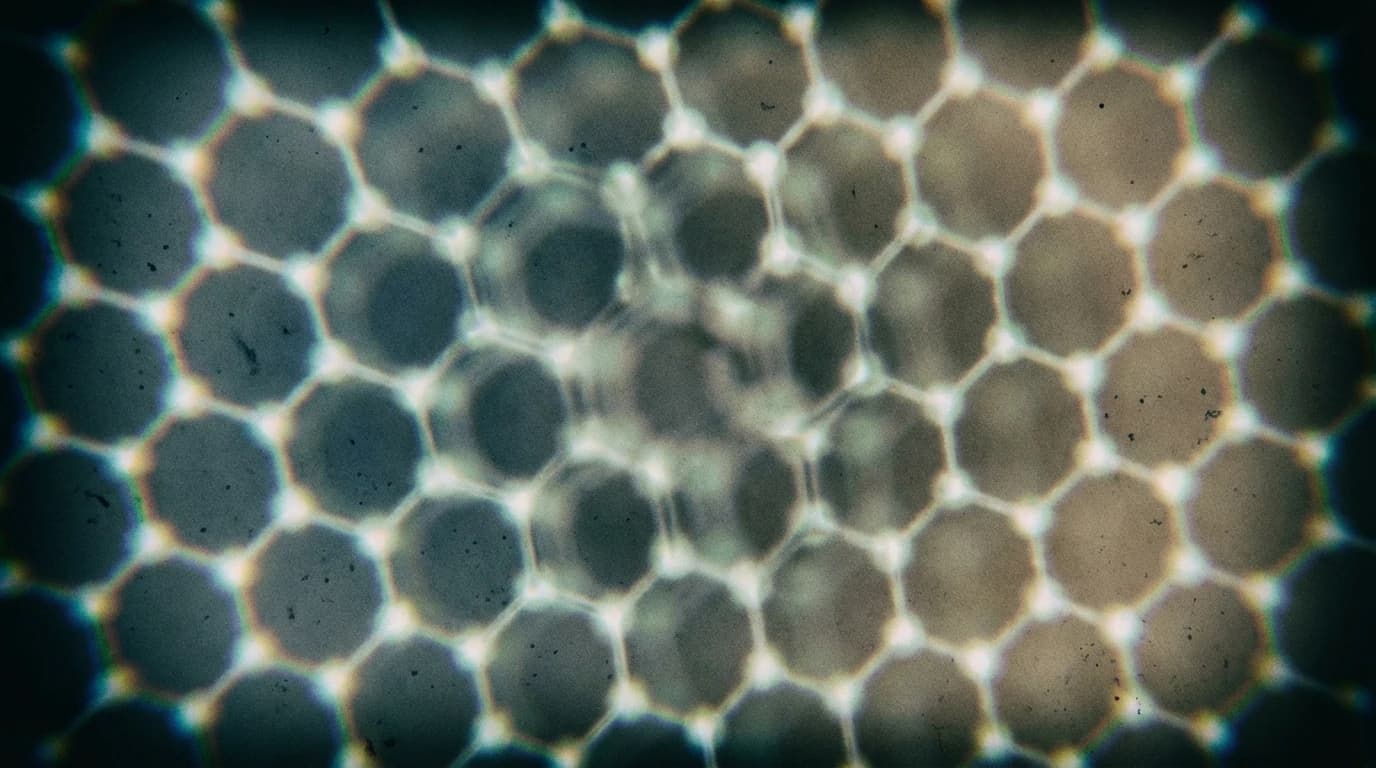

The solution may not lie in a new material alone, but in a force that bends it to our will. Using first-principles density functional theory (DFT), researchers investigated a new class of monolayers: MSi2PxAsy (where M is Molybdenum or Tungsten). The hero of this narrative is the perpendicular external electric field (Eext). When applied to these atomic sheets, the field acts as a master key, forcing the rigid atomic prison to open.

The data reveals a dramatic transformation. At an electric field strength of approximately 0.7 V Å-1, the material undergoes an identity crisis. It shifts from a direct bandgap to an indirect one. If the field intensity increases, the semiconductor collapses entirely, transitioning into a metal. This is a rare feat in solid-state physics—a material that can be toggled between conducting and insulating states without changing its chemical composition.

A Shapeshifting Future

The implications extend beyond simple conductivity. The study highlights a tunable Rashba spin splitting around the Γ point, which scales linearly with the external field. Furthermore, the field forces a redistribution of charge density, creating a type-II band alignment in homojunction structures. These findings suggest that the electronic properties of 2D materials are far more malleable than previously thought. Instead of building static chips, we might soon engineer flexible devices that adapt their fundamental nature on demand, servicing the next generation of spintronics and optoelectronics.