SLC12A3 Gene CRISPR Editing: A New Horizon for Gitelman Syndrome

Source PublicationKidney Research and Clinical Practice

Primary AuthorsLim, Fang, Cui et al.

Rare genetic disorders often languish in the backwaters of pharmaceutical development. For decades, patients with conditions like Gitelman syndrome have faced a therapeutic stagnation, relying on palliative electrolyte supplements rather than curative interventions. We have been stuck patching leaks instead of replacing the pipes. However, a recent study utilising SLC12A3 gene CRISPR technology suggests we are finally moving toward correcting the root cause.

Researchers focused on the SLC12A3 gene, which is responsible for the thiazide-sensitive sodium-chloride cotransporter (NCC). Mutations here drive Gitelman syndrome. The team employed CRISPR/Cas9 to perform a complete gene knock-in within WTC-11 human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). This is precision engineering. By integrating a functional copy of the gene, they created a new cell line, WTC-11SLC12A3-KI. To confirm success, they used a green fluorescence protein (GFP) reporter; if the cells glowed, the integration worked.

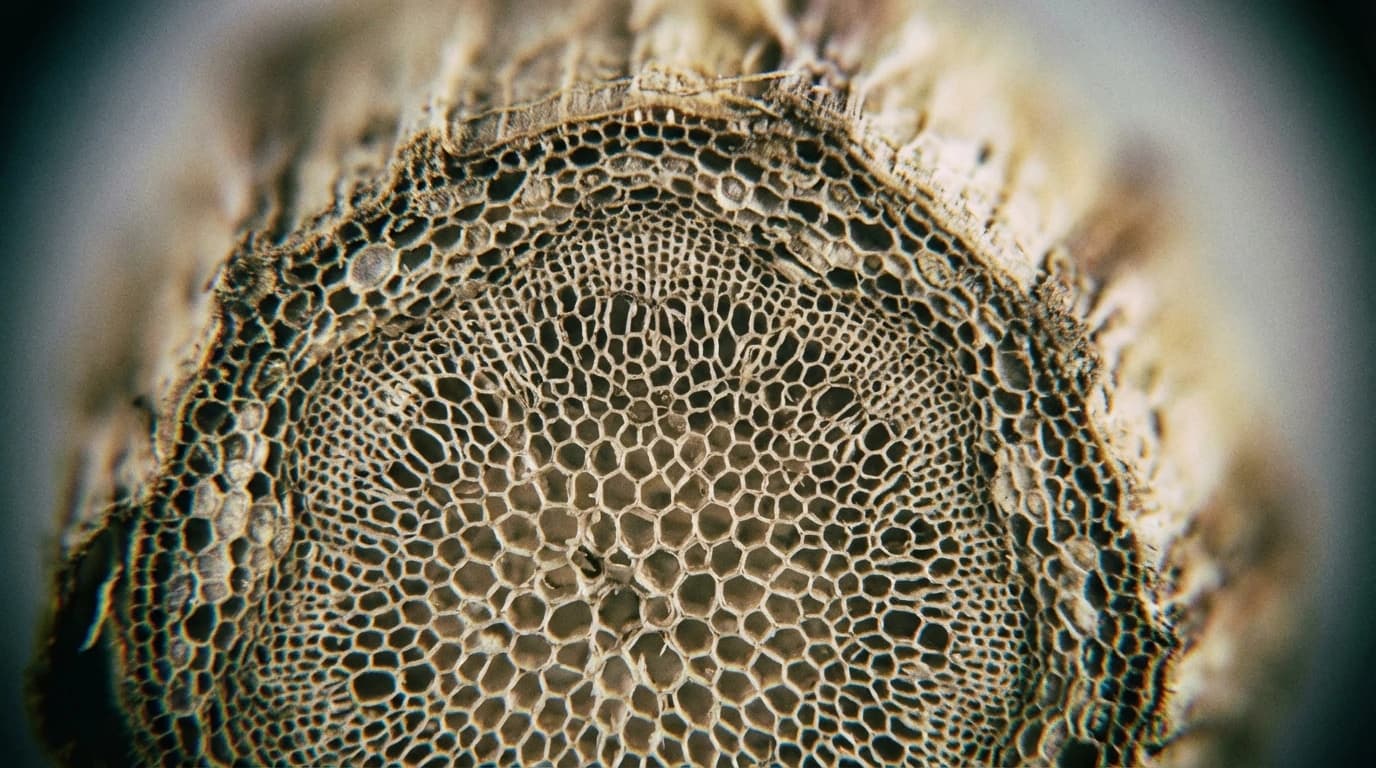

The measurements were distinct. The edited stem cells successfully differentiated into kidney organoids—miniature, three-dimensional tissue structures that mimic human organs. These organoids displayed elevated expression of the target protein compared to the parental line. Crucially, the study validated functionality within this organoid model. When treated with angiotensin II, the organoids demonstrated stimulated intracellular sodium flux, an activity that was effectively attenuated by thiazides in both the edited and control groups. This confirms that the engineered cells were not just holding the gene but that the introduced mechanism was physiologically active.

The trajectory of SLC12A3 gene CRISPR

While this specific application targets Gitelman syndrome, the implications extend far beyond a single diagnosis. We are witnessing the maturation of 'organoid-on-a-chip' models as viable testbeds for genomic medicine. If we can successfully edit and grow functional renal tissue in a dish, we can screen thousands of compounds against a patient's specific genetic architecture without risking their health.

This moves us away from the shotgun approach of generic drug discovery. Future programmes could utilise similar knock-in techniques to model other channelopathies or rare tubulopathies. Instead of relying on animal models that often fail to predict human renal toxicity, we can test efficacy on human tissue derived from gene-edited lines. The observation of increased WNK-SPAK/OSR1 signalling in a lab-grown organoid indicates that we might soon be able to modulate these pathways in living patients. This is the first step toward a clinic where the prescription is not a pill, but a genetic patch.