Rivers: The Hidden Arteries of Seabird Ecology

Source PublicationBiological Reviews

Primary AuthorsMorais, Chiaradia, Reina

Imagine a bustling port city where massive cargo ships arrive daily, offloading crates of fresh produce and essential supplies. The local population gathers at the docks because they know exactly where the resources are freshest and most abundant. If the ships stop coming, the city struggles. In the natural world, rivers function exactly like these cargo ships. They are not merely streams of water; they are nutrient highways dumping massive loads of biological wealth into the coastal ocean. This dynamic is central to seabird ecology, yet it has often been overlooked in favour of studying the open ocean. A recent review synthesised data from 51 different studies to understand exactly how these freshwater arteries support marine predators. The findings were stark. In 88% of the cases where scientists looked for a connection, they found one.

How river plumes drive seabird ecology

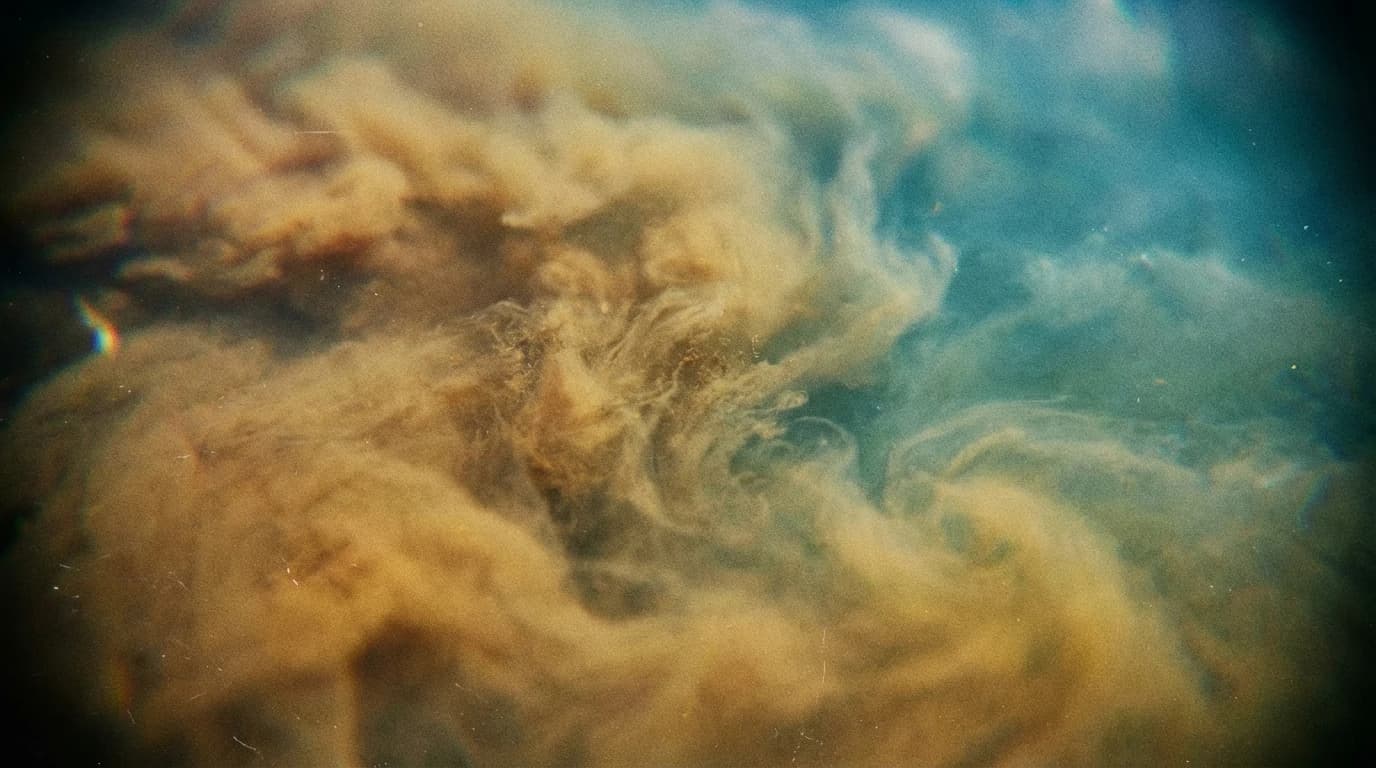

To understand the mechanism, we must look at the biological chain reaction. Think of a river plume—the cloudy water spreading out into the sea—as a visible dinner bell. If a river flows strongly, then it delivers a concentrated load of fresh water and nutrients to the coast. This creates a distinct habitat.

The process creates a predictable opportunity. First, the river inputs sustain the ecosystem. Second, the mix of waters supports a greater diversity of prey compared to the purely marine environment. Finally, seabirds flock to these areas, treating them as critical foraging hotspots. For a seabird, this is an all-you-can-eat buffet. Instead of searching the vast, empty ocean, they simply fly to the river mouth. The review found that when researchers used plume-based metrics as the primary way to explain bird behaviour, the evidence was conclusive 95% of the time. It is a highly reliable system.

A shelter from the storm

However, the port city analogy holds a darker truth. If the cargo ships bring hazardous waste along with the food, the locals get sick. Rivers drain vast areas of land, and consequently, while these estuarine areas are rich in food, the review notes they expose seabirds to potential pollutant burdens. The study highlights this trade-off: high reward, but higher risk.

Despite the pollution danger, the data suggests rivers provide a safety net. When the open ocean becomes hostile due to climate disturbances, rivers often exert a positive influence. They act as stable pockets of life. The review indicates that during these disturbances, seabirds may rely more heavily on these riverine environments to survive. As we look to the future, understanding these freshwater connections will be vital for protecting marine species in a rapidly warming world.