New Design Strategy Supercharges Magnetic Kagome Materials

Source PublicationNature Materials

Primary AuthorsCheng, Wang, Hao et al.

In standard wires, electrons often crash into obstacles, creating chaotic scattering. To build better electronics, physicists look for materials where electrons flow in a highly ordered state, rather than like cars in a traffic jam. A specific class of crystals known as magnetic kagome materials has long promised to facilitate this order, but they often suffer from internal magnetic conflicts.

Solving the Puzzle of Magnetic Kagome Materials

The term 'kagome' comes from a traditional Japanese basket-weaving pattern consisting of interlaced triangles and hexagons. In the quantum world, this geometry usually confuses electrons. They get 'frustrated'. They do not know which way to align. This magnetic confusion typically limits how well we can tune the material's properties.

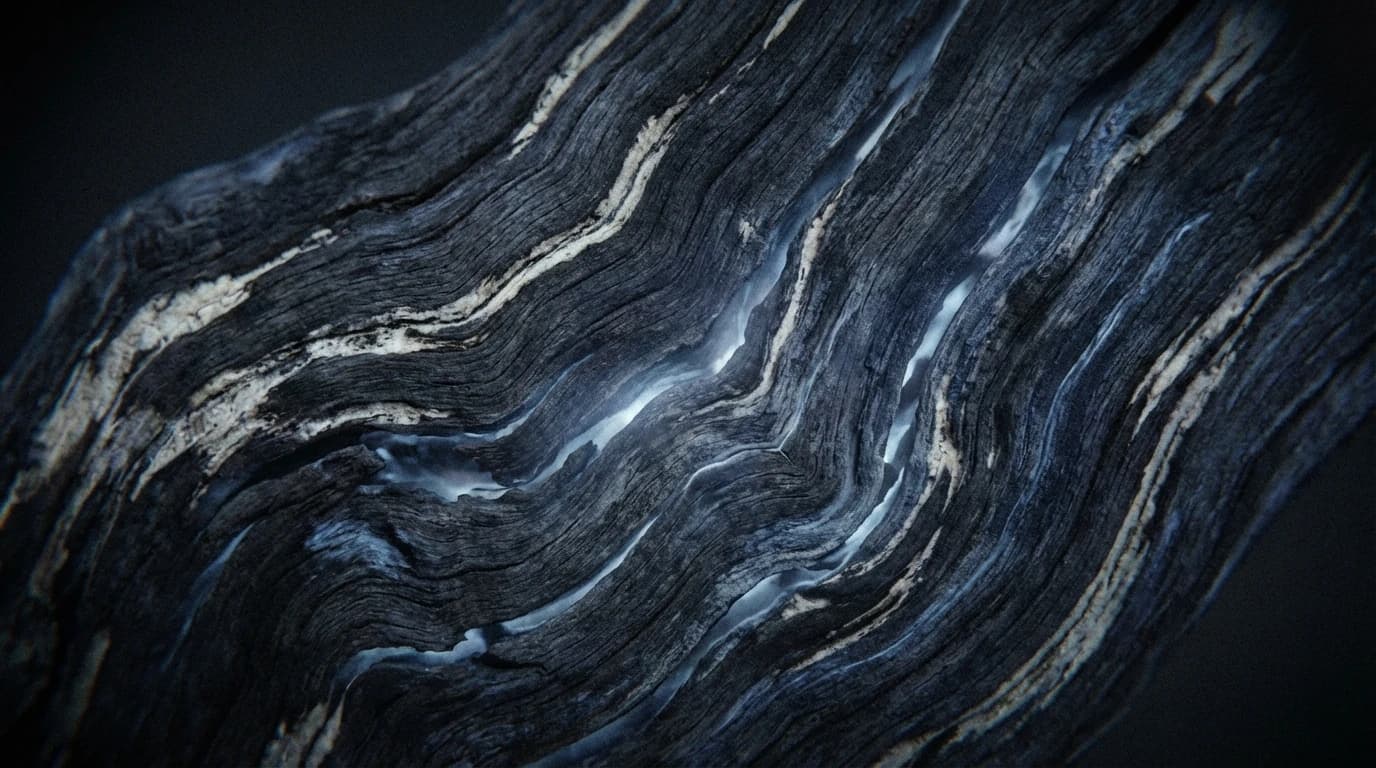

However, a new study introduces a clever workaround. The researchers synthesised a material called TbTi3Bi4. Instead of mixing everything together, they physically separated the components. They wove zigzag chains of magnetic Terbium (Tb) through bilayers of non-magnetic Titanium (Ti).

The mechanism is elegant. If you isolate the magnetic source from the path where electrons travel, then the geometric frustration is effectively bypassed. The magnetic influence remains strong, but it creates a cooperative environment rather than a conflicting one.

In this specific crystal structure, the team measured the results of this separation. They observed a 'giant' anomalous Hall conductivity—essentially, the material steers the electron flow sideways with immense strength and precision. The measurements revealed a conductivity of 105 Ω-1 cm-1, a figure that exceeds previous observations in similar frustrated metals. Spectroscopic analysis also identified a massive energy gap, confirming that the electrons had locked into a stable, ordered state.

These findings suggest that we do not need to accept the natural chaos of quantum magnets. By engineering the layers separately, we may be able to build components for next-generation computers that utilise these complex quantum states more effectively than current technology allows.