Moiré Polaritons: When Light Gets Dragged Through a Quantum Crowd

Source PublicationJournal of Physics: Condensed Matter

Primary AuthorsSantiago-García, Castillo-López, Ruiz-Tijerina et al.

Imagine walking through an empty station concourse. You move quickly, unimpeded. Now, imagine that same concourse packed with commuters. As you try to cross, you inevitably bump shoulders, slow down, and perhaps even drag a few people along in your wake. Your movement is no longer just about you; it is defined by your interaction with the crowd.

This is the best way to visualise the complex interactions described in a recent study on moiré polaritons.

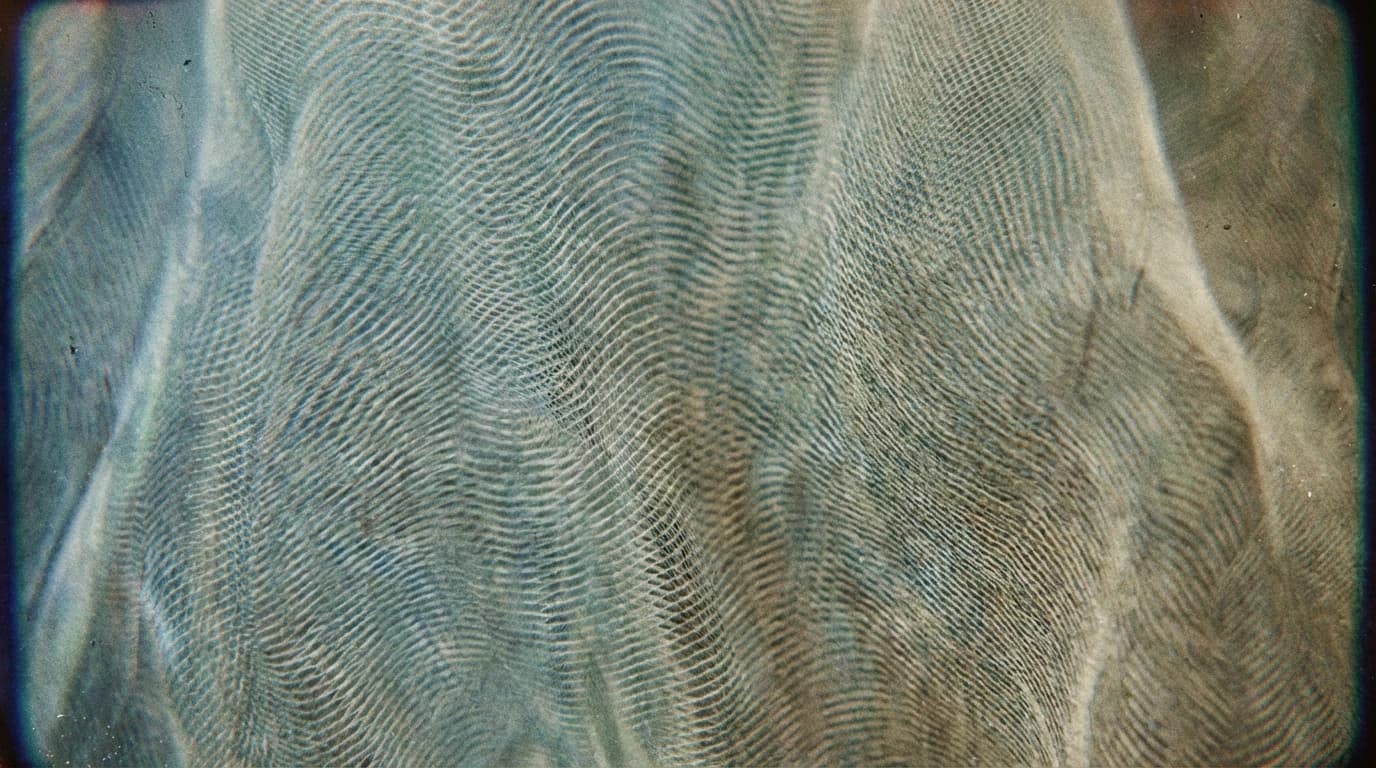

To understand the physics, we must first build the stage. If you take two sheets of chicken wire and layer them, then twist the top sheet slightly, you see a new, larger pattern emerge from the overlapping gaps. This is a moiré pattern. In the quantum world, scientists stack atomically thin materials to create a similar effect, resulting in a 'moiré superlattice'—a grid of energy pockets that can trap particles.

The mechanics of moiré polaritons

Inside these energy pockets, electrons and electron-holes pair up to form excitons (matter). When we shine a specific light on them, the excitons couple with photons (light) to become polaritons. These are hybrid particles: half-light, half-matter.

But the researchers in this study added a twist. They did not just look at a single polariton. They placed it inside a 'Bose-Einstein condensate'—essentially a dense, cold fog of dark excitons that do not interact with light. This is the crowd in our station analogy.

The study developed a variational approach to analyse this scene. The results suggest something fascinating happens to the moiré polaritons. They do not just pass through the fog; they disturb it.

If a polariton pushes away the surrounding dark excitons, it creates a bubble around itself. If it attracts them, it drags a cloud of particles with it. In physics, we call this getting 'dressed'. The polariton is no longer just a polariton; it becomes a 'moiré polaron-polariton'.

The model indicates that strong interactions within this system cause a significant shift in energy. It is like the difference in effort between sprinting on a track and sprinting through water. The resistance changes the runner's effective mass and speed.

Specifically, the authors demonstrate that this interaction leads to a stable, repulsive bound state. If you try to push these particles together, they push back. This implies that by controlling the density of the background 'fog', scientists could tune exactly how light and matter interact in these tiny lattices.