Microplastics Toxicity: Visualising Gut Stress in Marine Copepods

Source PublicationEnvironmental Pollution

Primary AuthorsDong, Wang

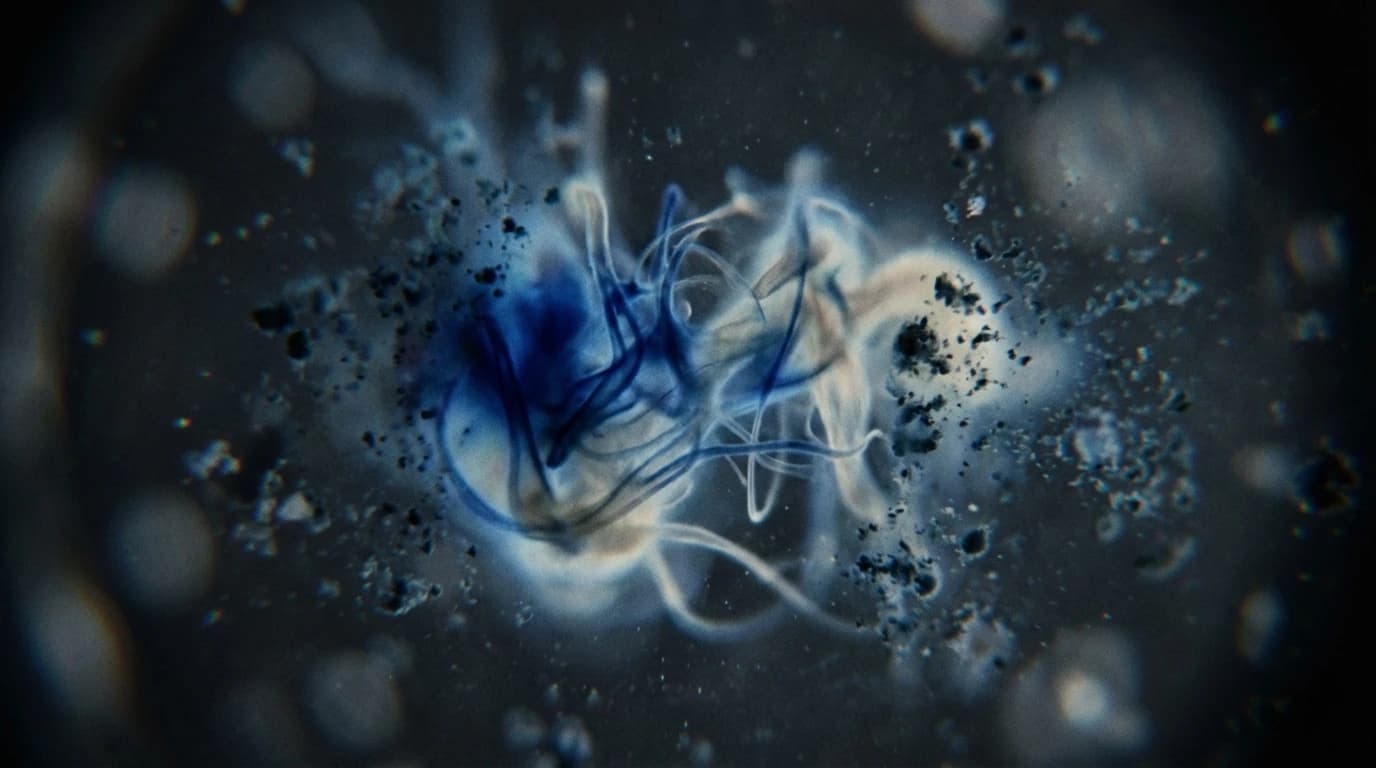

This laboratory analysis posits that exposure to micro- and nanoplastics (MNPs) disrupts the digestive physiology of the marine copepod Parvocalanus crassirostris. It is essential to note that these results rely on fluorescence imaging of labelled particles within a controlled setting, a method that provides precise data but may not perfectly replicate the chaotic variables of a dynamic oceanic environment.

Measuring Microplastics Toxicity and Gut Acidification

The methodology combined AIEgens-labelled probes with toxicological modelling. This allowed researchers to visualise pH gradients and Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) in real-time. The primary objective was to quantify microplastics toxicity by correlating particle burden with physiological stress. The data reveals a distinct spatial disparity. Both 5 μm microplastics (MPs) and 200 nm nanoplastics (NPs) increased acidity in the anterior midgut by 21.6% and 16.6%, respectively. Yet, the posterior gut saw a reduction in acidity. This inversion suggests a fundamental disturbance in the organism's digestive processing.

The Diatom Paradox and Oxidative Stress

The interaction between plastics and natural food sources yielded counter-intuitive data. When diatoms were introduced, MNP-induced acidification surged by 59.6%. However, the presence of food simultaneously alleviated ROS overproduction.

Stress levels varied significantly by particle size. Nanoplastics triggered a massive 58.8% systemic rise in ROS. Larger microplastics caused only a 10.4% increase. Modelling indicates that while MPs elicit stress at lower thresholds, NPs possess a higher ceiling for maximum oxidative damage. These findings suggest that sublethal impacts are highly dependent on particle size and nutritional context, though the long-term ecological consequences remain to be validated in field studies.