Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells and the Chaos of Nanoscale Terrain

Source PublicationACS Applied Materials & Interfaces

Primary AuthorsShilovskikh, Heffner, Du et al.

Is there not a strange elegance to the way biology thrives on disorder? A protein folds, a DNA strand twists around an error, and life carries on. Biology is messy. But move from the wet, organic world to the rigid geometry of photovoltaics, and that tolerance vanishes. Crystalline structures demand perfection. They do not adapt; they shatter.

A recent study highlights this fragility in CsPbI3, a material attracting serious attention in energy research. However, when researchers deposit it onto patterned indium tin oxide (ITO)—the conductive glass used in screens and panels—it often collapses. It reverts to its useless δ-phase almost immediately. Why does the crystal refuse to take hold?

Consider the genome for a moment. It is packed with redundancy. Evolution selects for organisms that can withstand a few mutations or a rough environment. It builds robust systems capable of error correction. A crystal lattice has no such history. It possesses no memory of survival, only the immediate thermodynamic demand for a low-energy state. If the floor is uneven, the structure fails. It is a fragile architect.

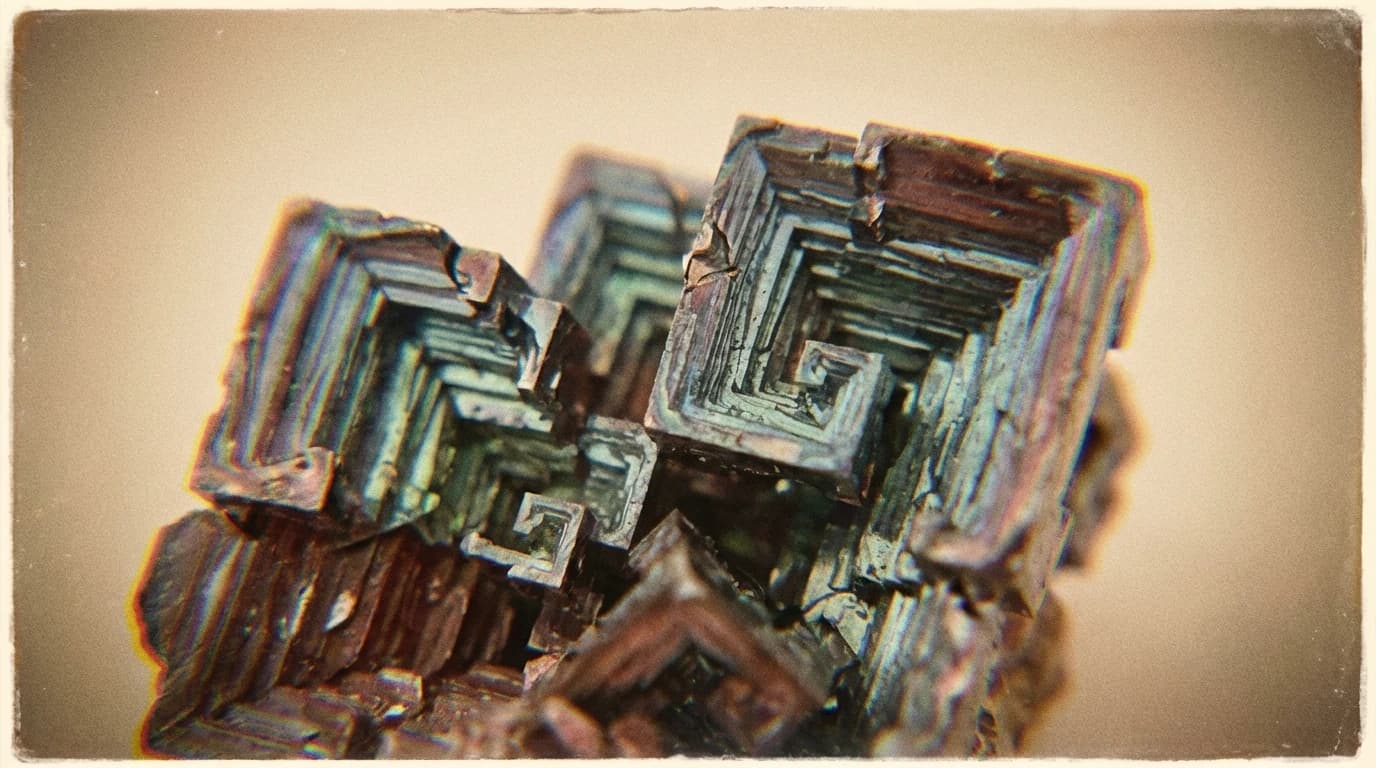

The researchers compared two ways of cutting the ITO glass: laser-patterning and chemical etching. Using scanning electron microscopy and electron backscatter diffraction, they observed that the degradation consistently began at the laser-cut edges. The laser leaves behind tiny imperfections—microcraters and steps merely 50 nanometres high. To a biological cell, that is nothing. To a growing crystal, it is a mountain range.

Why inorganic perovskite solar cells demand smooth terrain

The data shows these nanoscale ridges act as nucleation sites for the unwanted phase. The authors argue this topographical roughness drives thermal and structural changes, causing the crystal grains to coarsen and spoil. It appears that even a bump the size of a virus is enough to ruin the film. This sensitivity poses a significant challenge for inorganic perovskite solar cells. While organic hybrids have dominated headlines, the all-inorganic variants offer better thermal stability on paper. They should be the durable option. Yet, this study suggests that their durability is entirely dependent on the ground beneath them.

Chemical etching, which leaves a smoother finish, avoided this rapid decay. To build the solar panels of the future, we must stop treating the substrate as a passive table. It is an active participant. We cannot teach a crystal to evolve mechanisms for survival, but we can certainly smooth the path for it.