Fast Thinking: How Myelin Action Potential Conduction Synchronises the Brain

Source PublicationNature Communications

Primary AuthorsJamann, Montijn, Petersen et al.

Imagine you are stroking a velvet cushion. Your brain instantly marries the physical sensation from your fingertips with your internal knowledge of what 'soft' feels like. This seamless merger of touch and thought relies on split-second timing. A new study reveals that this synchronisation depends heavily on myelin action potential conduction.

These results were observed under controlled laboratory conditions, so real-world performance may differ.

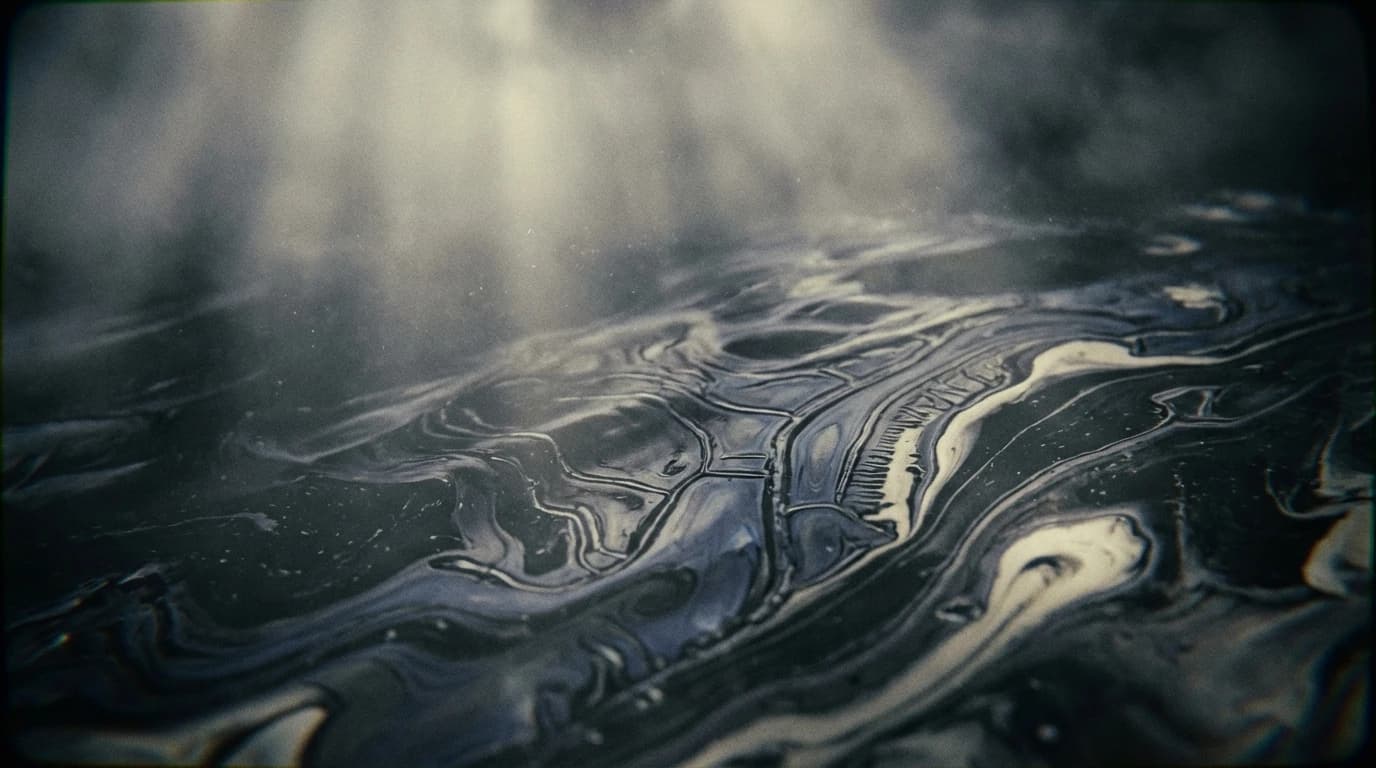

Myelin is the fatty insulation that wraps around our nerve fibres (axons). We have long known it acts like the plastic coating on an electrical wire, preventing signal loss. However, recent lab work suggests its function is far more specific. If the insulation holds, the brain keeps its rhythm. If it breaks, the music stops.

Disrupting Myelin Action Potential Conduction

Researchers investigated the pathway between the cortex and the thalamus in mice. They used a substance called cuprizone to strip away myelin, mimicking conditions found in demyelinating diseases. The team then measured how nerve impulses, or action potentials, travelled across the brain. The results were stark.

If the myelin is intact, the signal arrives on time. If the myelin is damaged, the signal arrives late and with significant 'jitter'.

The study measured that demyelinated nerves struggled specifically with high-speed bursts of information. The researchers describe this as a 'low-pass filter' effect. Imagine trying to shout a rapid tongue-twister through a long tube. If you speak slowly, the words arrive clearly. If you speak fast, the sounds blur together. Similarly, the study observed that while isolated neural spikes could get through, rapid-fire bursts were degraded.

Computational modelling further illuminated this mechanism. It suggests that without the saltatory (jumping) nature of conduction provided by myelin, the axon cannot recharge quickly enough to support high-frequency messages.

Finally, the team paired brain stimulation with whisker movements. They observed that intact myelin is vital for 'coincidence detection'. This is the brain's ability to notice when two things happen at the exact same moment. Consequently, the authors propose that myelin does not just speed up the brain; it creates the precise temporal window necessary for integrating complex information across long distances.