Evolution, Engineering, and the Future of Biodegradable Sensors

Source PublicationNature

Primary AuthorsLan, Li, Guo et al.

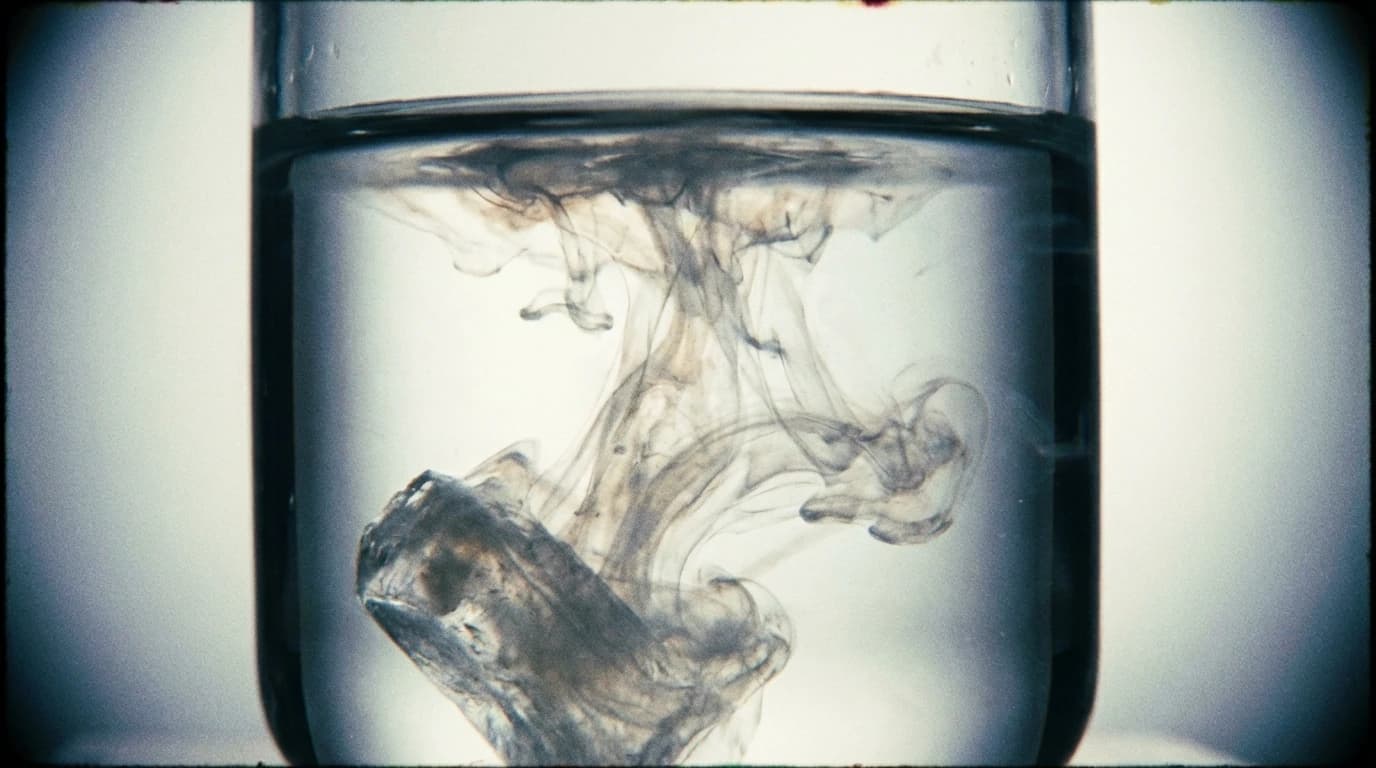

Is there anything quite as elegantly messy as the interior of a mammal? We tend to think of anatomy as a diagram in a textbook, clean and colour-coded. It is not. It is a squishy, shifting, wet environment where nothing stays still. This biological chaos is precisely why putting electronics inside the body is such a headache. Rigid silicon chips despise soft tissue. Batteries leak. Wires snap.

For years, the goal has been to create transient electronics—devices that do their job and then vanish. But these tools have been limited. They are often deaf and mute unless a reader is pressed directly against the skin. A new study, however, describes a soft, wireless system that overcomes these physical barriers, tested successfully in the abdominal cavity of horses.

The geometry of biodegradable sensors

The researchers tackled the two biggest enemies of implantable tech: distance and distortion. Most passive sensors (those without batteries) lose their signal if the body moves or if the reader is more than a few centimetres away. This new device, however, achieved a readout distance of up to 16cm. It did so using a 'pole-moving sweeping' readout system.

But the real intrigue lies in the shape. The team employed a folded structure to integrate mechanical flexibility with electromagnetic function. This is where the engineering begins to look suspiciously like biology. Nature realised billions of years ago that if you want to pack complex function into a cramped, moving space, you do not build straight lines. You fold. Consider the genome, or the tertiary structure of proteins. Folding allows for density. It allows a structure to bend without breaking.

By mimicking this logic, the biodegradable sensors maintained performance even when twisted or compressed. In the equine tests, the device reliably measured deep-tissue pressure and temperature. The choice of horses was deliberate; their large abdominal cavities mimic the depth required for human deep-tissue monitoring better than smaller rodents.

The data from the ex vivo experiments confirmed that the sensor could track strain accurately without needing strict positional control. This separates the study from previous attempts that required perfect alignment between the sensor and the reader. While the current results are specific to the prototypes tested, the design principles suggest a route toward implants that are not just biocompatible, but bio-mimetic in their geometry. We may soon see medical monitors that act less like machines and more like the tissues they inhabit.