Physics & Astronomy6 January 2026

Crowded Atoms: Visualising Low Energy Nuclear Reactions in the Lab

Source PublicationScientific Publication

Primary AuthorsLakesar, Pala, Rajeev

Imagine a Tokyo subway carriage during the absolute peak of rush hour. The carriage is the metal lattice of a solid material. The commuters are hydrogen atoms. Naturally, these commuters want their personal space; they push against one another to maintain a comfortable distance. In physics, we call this electrostatic repulsion.

Now, introduce the 'pushers'—the station staff whose job is to shove passengers inside until the doors barely close. If the pushers shove hard enough, and with a specific rhythm, the commuters are forced so close together that the normal rules of personal space collapse. They are squeezed until they occupy the same coordinate.

This is the fundamental concept behind **Low Energy Nuclear Reactions** (LENR).

In standard nuclear physics, fusing atoms requires the heat of a star to overcome that repulsion. It is violent. It is hot. But this study asks a different question: If we use a chemical 'pusher' to squeeze atoms into a metal 'carriage', can we get them to fuse without the heat?

The researchers set up an electrolysis cell to test this. They used light water and a nickel cathode. When they turned on the power (using half-wave rectified potentials of 5 V and 20 V), the electricity acted as the subway pusher. It drove hydrogen nuclei deep into the atomic framework of the nickel.

If you force enough hydrogen into the tiny gaps of the nickel lattice, the theory suggests that the metal electrons might screen the positive charge of the hydrogen. The 'personal space' barrier lowers. The atoms get uncomfortably close.

But how do you know if anything happened? You cannot see an atom fuse with the naked eye. You look for the debris.

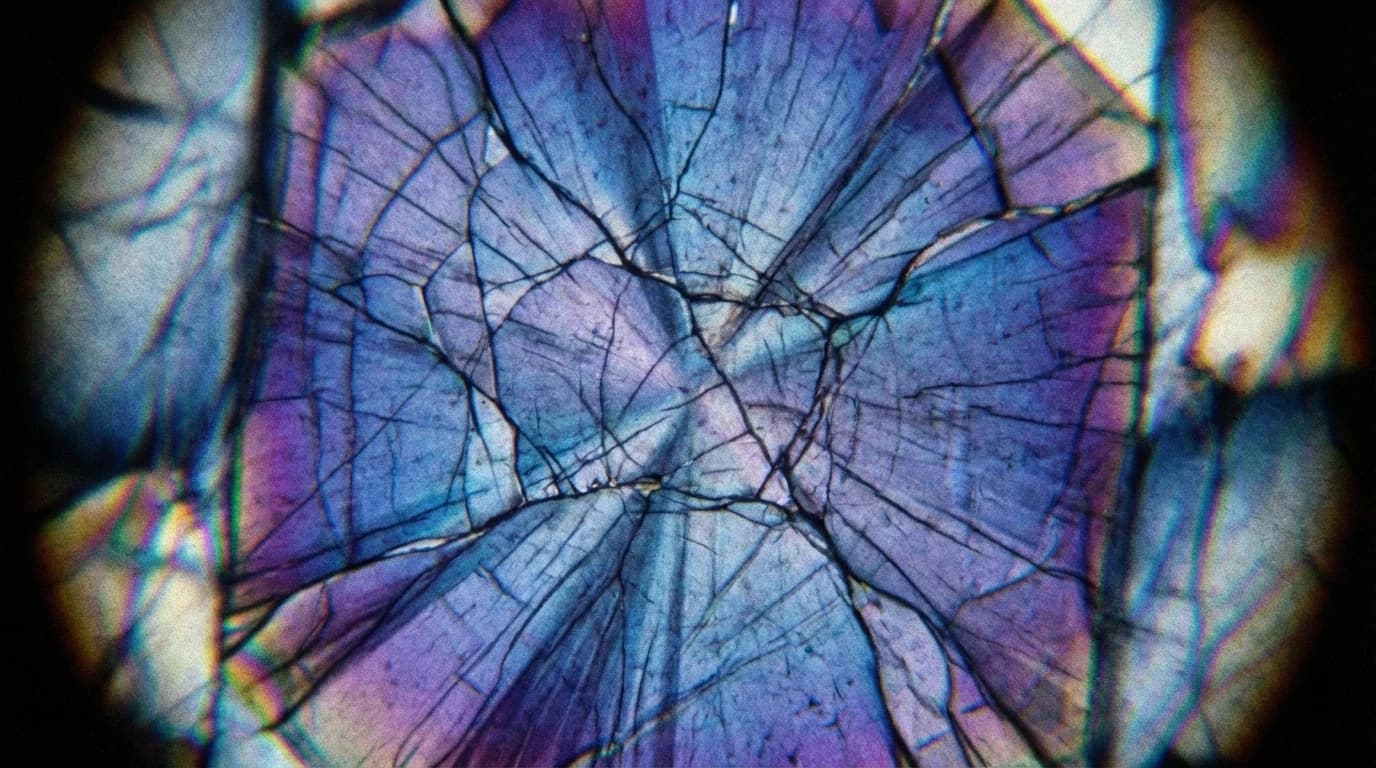

To detect this, the team used a Peltier-cooled diffusion-type Wilson cloud chamber. Think of this device as a pristine, foggy window. You cannot see a bullet fly through the air, but if it passes through a cloud of supersaturated vapour, it leaves a disturbance. The vapour instantly condenses along the path of the particle, creating a visible white streak, much like a jet plane leaves a contrail in the sky.

The results were stark.

The unreacted nickel samples sat in the chamber and did nothing. No tracks. No activity. Silence.

However, the nickel that had undergone the electrical 'shoving' told a different story. These samples emitted what appeared to be beta particles. The cloud chamber captured distinct condensation tracks ranging from 0.6 to 16 mm in length. The samples treated with higher voltage (20 V) were more active, showing an average of 1.0 counts per minute.

This is the critical separation between observation and theory. The study *measured* physical condensation tracks in a vapour chamber. This *suggests* that the electrochemical compression of hydrogen into nickel generated unstable isotopes which then decayed, ejecting high-energy particles. It implies that the crowded subway car didn't just get uncomfortable—it fundamentally changed the passengers.

Now, introduce the 'pushers'—the station staff whose job is to shove passengers inside until the doors barely close. If the pushers shove hard enough, and with a specific rhythm, the commuters are forced so close together that the normal rules of personal space collapse. They are squeezed until they occupy the same coordinate.

This is the fundamental concept behind **Low Energy Nuclear Reactions** (LENR).

In standard nuclear physics, fusing atoms requires the heat of a star to overcome that repulsion. It is violent. It is hot. But this study asks a different question: If we use a chemical 'pusher' to squeeze atoms into a metal 'carriage', can we get them to fuse without the heat?

How Low Energy Nuclear Reactions Work in the Lab

The researchers set up an electrolysis cell to test this. They used light water and a nickel cathode. When they turned on the power (using half-wave rectified potentials of 5 V and 20 V), the electricity acted as the subway pusher. It drove hydrogen nuclei deep into the atomic framework of the nickel.

If you force enough hydrogen into the tiny gaps of the nickel lattice, the theory suggests that the metal electrons might screen the positive charge of the hydrogen. The 'personal space' barrier lowers. The atoms get uncomfortably close.

But how do you know if anything happened? You cannot see an atom fuse with the naked eye. You look for the debris.

To detect this, the team used a Peltier-cooled diffusion-type Wilson cloud chamber. Think of this device as a pristine, foggy window. You cannot see a bullet fly through the air, but if it passes through a cloud of supersaturated vapour, it leaves a disturbance. The vapour instantly condenses along the path of the particle, creating a visible white streak, much like a jet plane leaves a contrail in the sky.

The results were stark.

The unreacted nickel samples sat in the chamber and did nothing. No tracks. No activity. Silence.

However, the nickel that had undergone the electrical 'shoving' told a different story. These samples emitted what appeared to be beta particles. The cloud chamber captured distinct condensation tracks ranging from 0.6 to 16 mm in length. The samples treated with higher voltage (20 V) were more active, showing an average of 1.0 counts per minute.

This is the critical separation between observation and theory. The study *measured* physical condensation tracks in a vapour chamber. This *suggests* that the electrochemical compression of hydrogen into nickel generated unstable isotopes which then decayed, ejecting high-energy particles. It implies that the crowded subway car didn't just get uncomfortable—it fundamentally changed the passengers.

Cite this Article (Harvard Style)

Lakesar, Pala, Rajeev (2026). 'Crowded Atoms: Visualising Low Energy Nuclear Reactions in the Lab'. Scientific Publication. Available at: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-8465270/v1