Chemistry & Material Science1 February 2026

Building Crystal Cities: A New Logic for DNA-functionalized Nanoparticles

Source PublicationChemPlusChem

Primary AuthorsWang, Ni, Yao et al.

Imagine a grand dinner party where ten thousand guests must find their specific, assigned seats. But there is a catch: everyone is blindfolded and thrown into the hall simultaneously.

Chaos ensues. People grab the nearest chair, bumping elbows and knocking over vases. Most guests end up at the wrong table. In physics, we call this a 'metastable state'. The system is stuck. It is stable enough that people stop moving, but it is not the *correct* arrangement.

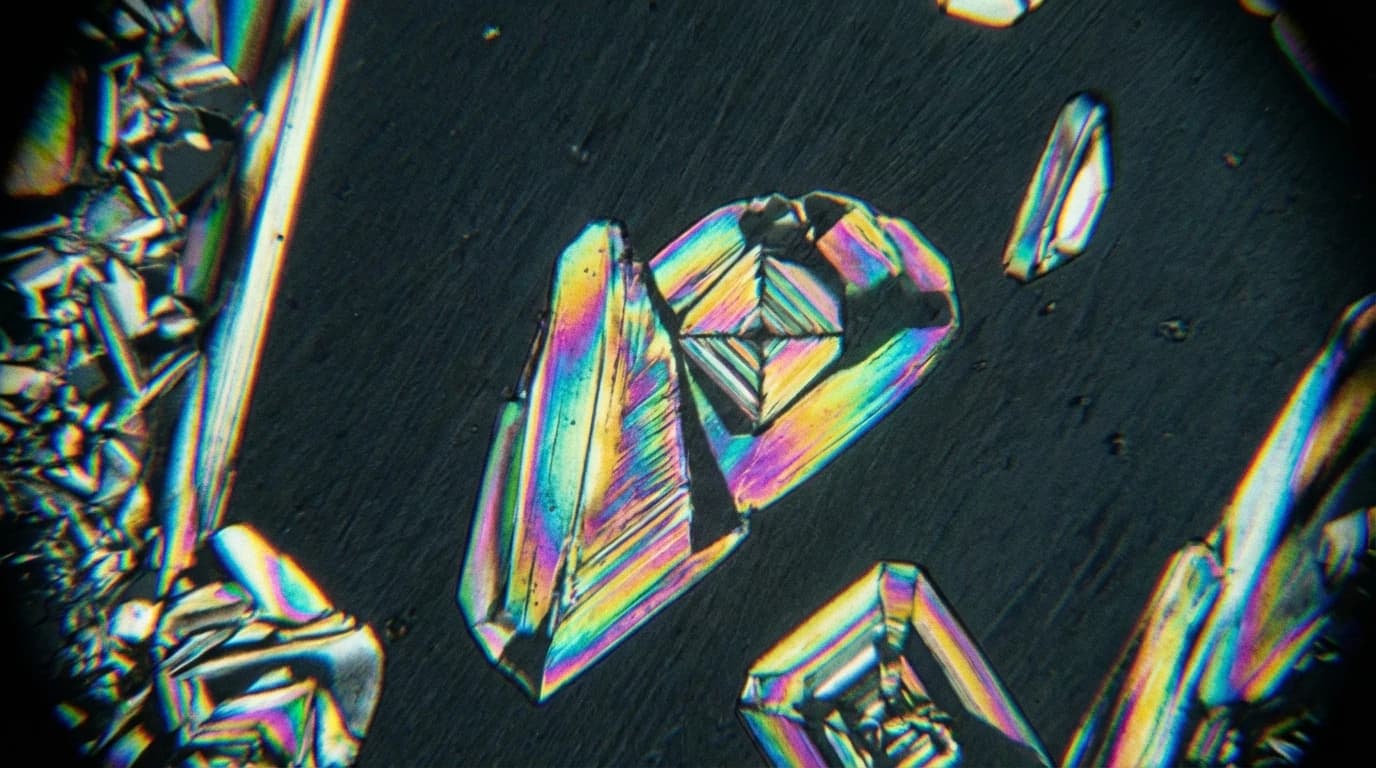

This is the exact problem researchers face when engineering crystals using **DNA-functionalized nanoparticles**. These are tiny particles coated in strands of genetic code, designed to act like 'programmable atom equivalents' (PAEs). We want them to self-assemble into perfect, long-range 3D structures. Often, they just form a messy pile.

The Old Way: Shaking the Room

For years, the solution was brute force. In our dinner party analogy, this would be 'thermal annealing'. You effectively heat the floor until it burns the guests' feet. They jump up, run around in a panic, and eventually, as you slowly cool the floor, they hopefully settle into the correct chairs. While effective, high heat can damage sensitive biological components. It is aggressive. It requires energy. Researchers needed a way to reorganise the room without setting it on fire.How DNA-functionalized Nanoparticles Use 'Toeholds'

The concept paper discusses a more elegant solution: catalytic assembly using 'toehold-mediated strand displacement'. Think of this as a polite usher walking through the party. If a guest is in the wrong seat, the usher does not shout. Instead, they spot a 'toehold'—a small, exposed section of the guest's ticket (or DNA strand). **If** the usher grabs this toehold, **then** they can smoothly peel the guest away from the wrong chair. The mechanism works step-by-step:- The Mismatch: A particle is bonded to a neighbour, but the bond is not quite right. A small tail of DNA is left hanging loose.

- The Toehold: A displacement strand (the catalyst) latches onto this loose tail.

- The Zip: The new strand binds stronger than the old one, zipping the old connection open.

- The Swap: The particle is released, free to move to its correct position in the crystal lattice.

Cite this Article (Harvard Style)

Wang et al. (2026). 'Isothermal Catalytic-Assembly of DNA-Mediated Nanoparticle Superlattices Programmed by DNA Strand-Displacements and Organic Solutes.'. ChemPlusChem. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/cplu.202500680